Photo by Rae Threat

A Special Issue of AG About Gender: International Journal of Gender Studies

Edited by Lynn Comella (Ph.D., University of Nevada, Las Vegas) and Mariella Popolla (Ph.D., University of Genoa, Italy).

Deadline extended to 10 May 2019

Pornography is one of the most popular and profitable forms of popular culture in the world. A multi-billion-dollar industry, it puts on stage not just sexuality, but broader social processes and forms of knowledge about gender, race, class, desire, aesthetics, technology, politics and the law.

Considering just how widespread pornography’s popularity is, it is surprising that scholars do not know more about its history, industrial organization and modes of production and consumption, including what it means to labor within a rapidly changing and increasingly decentralized global industry. Those working and publishing in the field of porn studies must also contend with the fact that pornography continues to be seen by many as a self-evident “problem” in need of a solution, rather than a complex set of cultural practices that deserve to be studied with the same rigor reserved for other, less unruly subjects (Attwood 2005).

Pornography is ultimately “not a thing but a concept,” a thought structure that “names an imaginary scenario of danger and rescue” in which the players may change, but the melodrama remains remarkably consistent over time (Kendrick 1987, xiii).

How might our ideas about pornography change by rethinking, and indeed queering, the relationship between gender and agency and unmooring these concepts from their essentialist and heteronormative frameworks?

Since the early days of the feminist sex wars the issue of gender has loomed large in discussions about pornography and its effects (Vance 1984; Duggan and Hunter 1995; Jensen 2007; Dines 2010). Pornography has historically been perceived as a “guy thing,” an industry by and for men that relies on the sexual subjugation of women to make a profit. This formulation of pornography’s “problem” as primarily one of gender and power—men’s porn consumption negatively impacts women—has subsequently influenced a great deal of writing about, research on, and clashes over pornography.

In the 1970s, for example, antipornography feminists argued that the pornography industry fostered a cultural climate that was hostile toward women (Bronstein 2011). Andrea Dworkin theorized that pornography “conditions, trains, educates and inspires men to despise women, to use women, to hurt women” (1980, 289). Susan Brownmiller argued it was the “undiluted essence of anti-female propaganda” (1980, 32). Robin Morgan famously asserted that “pornography is the theory and rape is the practice” (1980, 139). According to Catharine MacKinnon pornography shows us that “what men want is: women bound, women battered, women tortured, women humiliated, women degraded and defiled, women killed” (1989, 326-327).

Pornography was dangerous, they averred; it inspired misogyny and violence toward women and active measures were needed to curb its availability.

Anti-censorship writers, activists, and academics responded, arguing that the realm of sexual representation and entertainment could not be reduced solely to sexual danger while ignoring the realm of female pleasure (Vance 1984). They pushed back against essentialist understandings of gender and sexuality that presented women and men as homogenous and undifferentiated groups. They countered efforts to present men as sexual agents and women passive victims and objected to the idea that men were visual creatures, but women were not. They also pointed to the sexual double standard that claimed men were entitled to publicly accessible forms of sexual entertainment, but women’s pleasures were expected to remain tethered to the privacy of the home, domesticated and divorced from the realm of commercial sexuality (Rubin 1993; Juffer 1998; Thompson 2015).

The rigidity of these arguments, including the heteronormative gender hierarchy they naturalized, persist today, limiting how we think about and examine the sexual subjectivities and experiences of female, queer, and transgender porn producers and consumers (Rydberg 2015; Neville 2018). They also limit our understanding of the mainstream heterosexual porn industry. Scholars have noted, for example, that the overwhelming focus on male porn consumption and its effects have made it difficult to acknowledge that women themselves might be porn consumers and that “social stigma, restricted modes of access and a lack of ‘women-oriented’ material (rather than a lack of interest) have been reasons why women have not been such ‘visible’ porn consumers” (Mowlabocus and Wood 2015). Queer and transgender pornography, similarly, have the potential to subvert hegemonic discourses of gender and sexuality (Koller 2015; Trouble 2015; Lee 2014).

In recent years researchers, writers, and adult industry practitioners have begun to pay greater attention to these questions. The Feminist Porn Awards (2006-2015), for example, was created to celebrate and honor diversity and inclusiveness in pornography. The publication of the groundbreaking The Feminist Porn Book, moreover, brought together work by porn scholars and porn producers to discuss the myriad cultural practices and processes involved in “producing pleasure” (Taormino, Shimizu, Penley, and Miller-Young 2013).

This special issue of AG-About Gender looks to continue these conversations. We are looking for articles that engage with pornography’s complex relationship to gender, agency and power, including empirical analyses and theoretical discussions from across the disciplines that draw upon intersectional frameworks. We actively seek research contributions from both scholars and those who work within the industry. Papers may include, but are not limited to, a focus on the following:

- Global Contexts of Production, Distribution, and Consumption, especially in Non- Anglo Contexts;

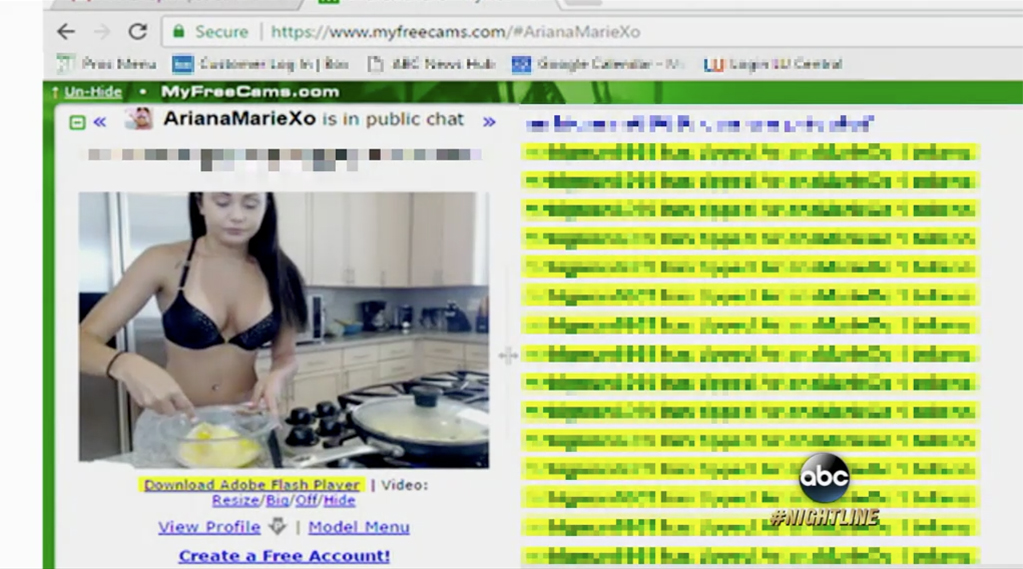

- Digital Pornographies;

- Sexual Labor and Industrial Practices;

- Gender and Spectatorship;

- Sex Panics and their Effects;

- Theories of Objectification, Intimacy and Affect;

- Feminist, Queer, Post Porn, and Transgender Pornographies;

- Pornographies and the Law;

- Masculinities and Pornographies

Papers should be between 5000 and 8000 words (excluding bibliography). Languages: English, Spanish, Italian.

Please follow the instructions gathered in the Author’s guidelines.

Contributions should be accompanied by: a brief abstract (maximum length: 150 words); some keywords (from a minimum of 3 to a maximum of 5). Abstract and keywords should both be in English. All texts must be transmitted in a format compatible with Windows (.doc or .rtf), following the instructions provided by the Peer Review Process. Please see the journal’s author guidelines. https://riviste.unige.it/aboutgender/about/submissions#authorGuidelines

Contributions must be sent by 10thMay 2019. Approximate timetable for the publishing process:

1. period October 2018/May 2019 – articles proposal

2. period May 2019/June 2019 – double blind peer review

3. period July 2019/August 2019 – revising of the articles according to the reviewers’ comments

4. period August 2019 / September 2019 – final editing

5. October 2019 – publishing